By Louis J Kruger

Summary: After 20 years of the MCAS graduation requirement, the debate about requiring high school students to pass the MCAS tests will soon reach a crescendo. Next November, voters may be asked on a statewide ballot to decide if the graduation requirement will be discontinued. Against this backdrop, it is important for voters to know if the graduation requirement has adversely impacted Massachusetts’ overall high school graduation rate and the graduation rate of historically underserved students.

During the two decades prior to the pandemic (2000-2019), Massachusetts‘ overall high school graduation rate improved at a slower pace than the U.S. high school graduation rate. However, focusing on Massachusetts’ overall graduation rate obscures what is happening to students from historically underserved groups. Massachusetts’ graduation gaps for Latinx, Black and low-income students and English learners are all larger than the national average gaps for these students. The aforementioned student groups disproportionately fail the 10th grade MCAS tests required for a high school diploma. Furthermore, research indicates that failing a high school exit exam, such as the MCAS, even once negatively impacts the graduation rate of academically and economically challenged students. The data and research suggest that (a) the entire story about Massachusetts’ graduation rates is a far cry from the overly rosy one presented by proponents of the MCAS graduation requirement; and (b) the MCAS graduation requirement is a likely impediment to Massachusetts’ improving its graduation rate.

High school graduation rates are often used as important indicators of the success or failure of statewide education policies. This is understandable given that many jobs require at least a high school diploma and unemployment is higher for individuals without that degree. Given the importance of the graduation rate, proponents of the MCAS graduation requirement have attempted to use graduation data to support this policy and assert that the graduation requirement has not been a major impediment to obtaining a diploma.

For example, on September 13, 2023, Associate Commissioner of Massachusetts Education Robert Curtin presented a graph of the Massachusetts high school graduation rate from 2006 to 2022 to the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. He said the MCAS could not be a major obstacle to students graduating from high school because the graph showed that the graduation rate had gone up. In a February 2024 report (MCAS, NAEP and Educational Accountability) sponsored by the Pioneer Institute, a similar graph appeared. The author, Cara Candal, used it as a basis for asserting that test-based accountability motivates teachers and students and “helps close access and outcome gaps” among students. In a MCAS debate hosted by Boston College’s Law School on November 4, 2023, Edward Lambert, Executive Director of the Massachusetts Business Alliance for Education, cited the Massachusetts’ high school graduation rate in his defense of the MCAS graduation requirement. He said that during the MCAS era, Massachusetts’ “graduation rates went up, and they continued to rise.”

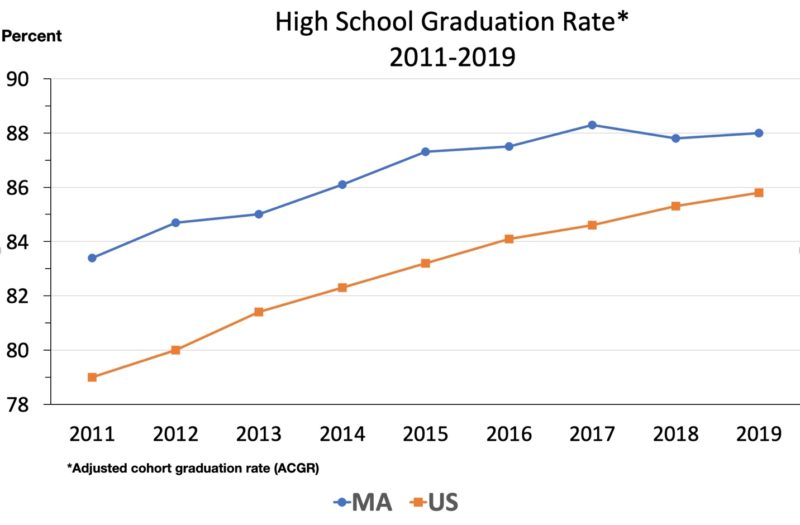

Although that is true, Curtin, Candal and Lambert all failed to mention that rates have gone up across the country and the national high school graduation rate has gone up faster than Massachusetts’ rate. During the period of 2000 to 2010 when the Averaged Freshmen Graduation Rate (AFGR) method was used for calculating high school graduation rates, the U.S. gained 6.5 percentage points in its graduation rate (from 71.7% to 78.2%), whereas Massachusetts gained only 4.6 percentage points (from 78.0% to 82.6%). In 2011, the federal government replaced the AFGR with the Adjusted Cohort Graduation Rate (ACGR)*. Using this latter method for the 2011 to 2019 time period (2019 was the last full school year prior to the pandemic), the U.S. gained 6.8 percentage points (from 79.0% to 85.8%), whereas Massachusetts increased its graduation rate only 4.6 percentage points (from 83.4% to 88.0%).

Massachusetts’ graduation rate has always been above the national average, which is unsurprising since Massachusetts families rank among the highest in both income and education. However, what is surprising is how little progress Massachusetts has made in its high school graduate rate relative to the other states. In 2000, Massachusetts had the 13th highest graduation rate in the country, and by 2019 our state had slipped to 15th.

In 2019, eight states had met or exceeded a graduation rate of 90%. Massachusetts’ was not one of them. Therefore, it is difficult to argue that Massachusetts’ relatively slower pace of improvement in its graduation rate was the result solely of ‘hitting a ceiling’ of what was possible to attain. Given that Massachusetts’ 2019 scores on the Nation’s Report Card (National Assessment of Educational Progress) placed it first in the nation on three of the four tests, how did it come to pass that the state with highest test scores ranks only 15th in high school graduation? It begs the question of what is preventing some of our students from graduating on time.

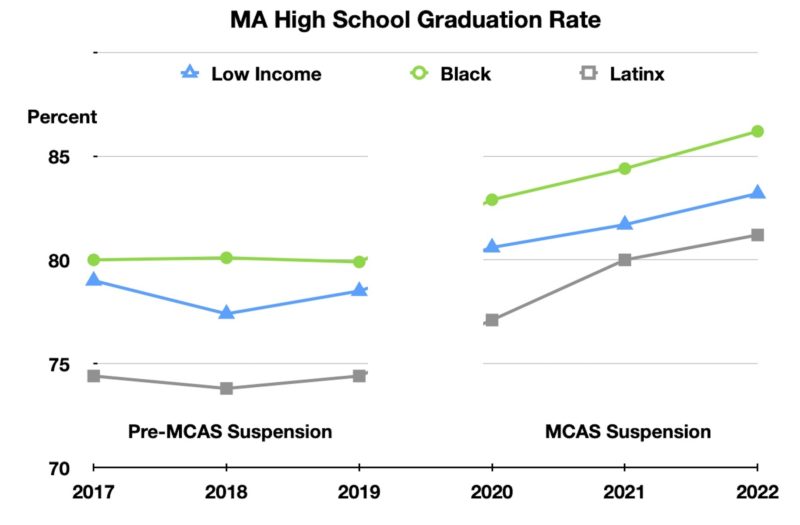

Lambert is correct about the Massachusetts graduation rate continuing to rise only if he includes the years of 2020 to 2022, when the MCAS graduation requirement was suspended. During the three years (2017 to 2019) immediately preceding the suspension of the MCAS graduation requirement, Massachusetts’ graduation rate had plateaued, dropping a fraction of a point (-0.3%). In contrast, during the subsequent three-year suspension of the MCAS graduation requirement, the graduation rate rose 2.1 percentage points. After only two years of the suspension, Massachusetts’ graduation rate leaped from 15th to 5th in the nation (As of this writing, national and complete state graduation data for the third year, 20022, had not yet been published). In referencing their graphs, neither Curtin nor Candal provided the caveat that the significant rise in the graduation rate during the years from 2020 to 2022 occurred while the MCAS graduation requirement was suspended.

It should be acknowledged that the suspension of the graduation requirement is not the only possible cause of the increase in Massachusetts’ graduation rates during the pandemic. Other graduation requirements, such as attendance, were also relaxed for three years. However, the MCAS graduation suspension is the most likely cause. Most other states also relaxed their graduation requirements during the pandemic and yet the national graduation rate improved only 0.3% (from 85.8% to 86.1%) during the first two years of the pandemic, whereas Massachusetts’ graduation rate improved 1.8% (from 88% to 89.8%).

The increase in Massachusetts’ graduation rate during the suspension of the MCAS graduation requirement was largely driven by students who disproportionately fail the MCAS. During the suspension of the requirement, the increase in graduation rates of Black (6.3%), Latinx (6.8%) and low-income students (4.7%) and students with disabilities (4.1%) and English learners (8.5%) were all higher than the 2.1 percentage point increase for the state. Furthermore, the increase in graduation rates of these historically underserved students during the three-year MCAS suspension far exceeded what occurred to their graduation rates during the three years prior to the suspension. In fact, graduation rates had not improved at all for Black, Latinx and low-income students during the three years immediately preceding the suspension.

The pattern of Massachusetts’ graduation rates during these six years (2017-2022) is consistent with the assertion that MCAS graduation requirement is holding back historically underserved students from graduating on time. The above data and this assertion are also consistent with research on test-based accountability and graduation rates. Most of these studies have found that high school exit exams, such as the MCAS, have a negative impact on graduation rates, particularly among historically underserved students (Dee & Jacob, 2007; Helmet & Marcotte, 2013; Ou, 2009; Papay, Murnane & Willett, 2010; Papay, Mantil & Murnane, 2022; Warren et al., 2006 ) ( A study in California, Reardon et al., 2010, and another in Texas, Martorell, 2005, failed to find this effect.) Especially noteworthy for the purpose of this paper, the studies in Massachusetts (Papay, Murnane & Willett, 2010; Papay, Mantil & Murnane, 2022) found that barely failing the high school math MCAS exam in 10th grade caused a reduction in the graduation rate of low-income urban students.

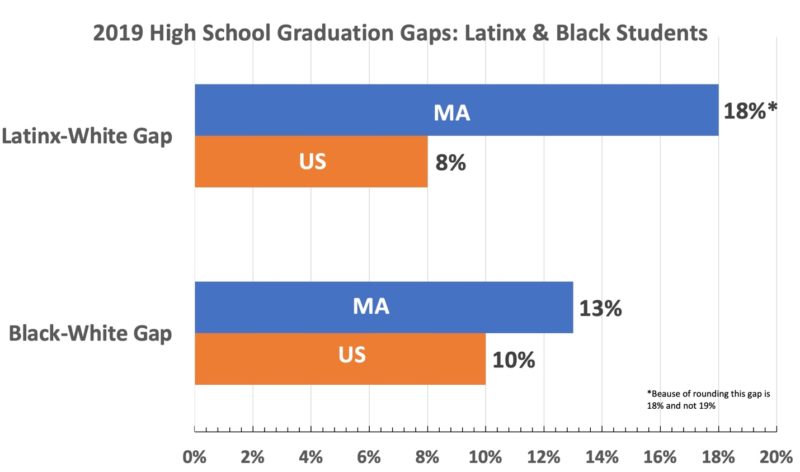

Given the above results, it seems likely that the MCAS graduation requirement is a factor in Massachusetts’ large graduation gaps. In 2019 Massachusetts had the fifth largest graduation gap in the nation between Latinx and White students (74% vs 93%), and the sixth largest graduation gap between English learners and non-English learners (65% vs 91%). Massachusetts also had graduation gaps that were larger than the average national gaps for Black and White students (80% vs 93%), and low-income and non-low-Income students (79% vs 94%).

Latinx, Black and low-income students, and especially English learners disproportionately fail the MCAS, and students who failed the MCAS in 2019 were 21 times more likely to drop out than those who passed the exams.

The data and research are clear. Contrary to the contention of the proponents of the MCAS graduation requirement, the requirement is disproportionately preventing students from historically underserved groups from graduating on time. While other states rapidly increased their graduation rates, Massachusetts failed to keep pace because of an albatross around its neck, the MCAS graduation requirement. Given the research indicating that high school exit exams do not raise academic achievement (Holme et al., 2010; Poquette & Butler, 2018), it is time to end the MCAS graduation policy and stop denying many of our most vulnerable students a high school diploma and a path to a better life.

*The US transitioned to the ACGR method in 2011 because it was deemed slightly more accurate than the AFGR. During several overlapping years, the average difference between the two measures in Massachusetts was less than one percentage point.

References

Atwell, M., Balfanz, R., Manspile, E., Byrnes, V., & Bridgeland, J. (2021) Building a Grad Nation: Progress and Challenge in Raising High School Graduation Rates. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED617355

Atwell, M., Balfanz, R., Byrnes, & V., & Bridgeland, J. (2023) Building a Grad Nation: Progress and Challenge in Raising High School Graduation Rates. Retrieved from https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/items/fe488368-d105-4194-87bf-a9f6521efa90/full

Barnum, M., Belsha, K., & Wilburn, T. (January, 2022). Graduation rates dip across U.S. as pandemic stalls progress. Chalkbeat. Retrieved from https://www.chalkbeat.org/2022/1/24/22895461/2021-graduation-rates-decrease-pandemic/

Candal, C. (2024). MCAS, NAEP and Educational Accountability. Retrieved from https://pioneerinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/PNR-548-MCAS-NAEP-Accountability-WP-v04.pdf

Dee, T., & Jacob, B.A. (2007). Do High School Exit Exams Influence Educational Attainment or Labor Market Performance?. In A. Gamoran (Ed), Standards-Based Reform and Children in Poverty: Lessons for “No Child Left Behind”. Brookings Institution Press.

Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Kalogrides, D. (2009). State high school exit examinations and NAEP long-term trends in reading and mathematics, 1971-2004. Educational Policy, 23(4), 589–614.

Hemelt, S. W., & Marcotte, D. E. (2013). High school exit exams and dropout in an era of increased accountability. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 323–349.

Ou, D. (2010). To leave or not to leave? A regression discontinuity analysis of the impact of failing the high school exit exam. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), 171–186.

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2019). Spring 2019 MCAS Tests: Summary of State Results. Retrieved from https://archives.lib.state.ma.us/bitstream/handle/2452/808673/ocn753986717-2019.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2019). Cohort 2019 Four-Year Graduation Rates – State Results. Retrieved from https://www.doe.mass.edu/infoservices/reports/gradrates/2019-4yr.docx

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (2023). Cohort graduation rates. Retrieved from https://profiles.doe.mass.edu/grad/grad_report.aspx

Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (nd). Public High School Dropout Summary 2019. https://www.doe.mass.edu/infoservices/reports/dropout/2018-19/

Martorell F. (2005). Does failing a high school graduation exam matter? Unpublished manuscript, UC Berkeley.

McFarland, J. (2019). What is the difference between the ACGR and the AFGR? Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/blogs/nces/post/what-is-the-difference-between-the-acgr-and-the-afgr

McHugh, M. (2009). The odds ratio: Calculation, usage and interpretation. Biochemica Medical, 19 (June, 2).

National Assessment of Educational Progress (nd). Data retrieved from https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/ndecore/xplore/NDE

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Public High School Graduation Rates. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/coi.

National Center for Education Statistics. (2022). Employment and Unemployment Rates by Educational Attainment. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/coe_cbc.pdf

National Center for Education Statistics (2015). Public high school averaged freshman graduation rate (AFGR), by state or jurisdiction: Selected years, 1990-91 through 2012-13. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19/tables/dt19_219.35.asp

National Center for Education Statistics (2010). Averaged freshman graduation rates for public secondary schools, by state or jurisdiction: Selected years, 1990-91 through 2007-08. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d10/tables/dt10_112.asp

Papay, J. P., Mantil, A., & Murnane, R. J. (2022). On the Threshold: Impacts of Barely Passing High-School Exit Exams on Post-Secondary Enrollment and Completion. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 44(4), 717–733.

Papay, J. P., Murnane, R. J., & Willett, J. B. (2010). The consequences of high school exit examinations for low-performing urban students: Evidence from Massachusetts. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(1), 5–23. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373709352530

Poquette, H. & Butler, A. (2018). Understanding the Policy Context of High School Exit Exams: A Review of the Literature from 2006 to 2018. Working Paper. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED604192

Reardon S. F., Robinson J. P. (2012). Regression discontinuity designs with multiple rating-score variables. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 5(1), 83–104.

United States Census Bureau (2022). https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US,MA/INC11022

Warren, John R., Jenkins, Krista N., Kulick, Rachael B., 2006. High school exit examinations and state-level completion and GED Rates, 1972–2002. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 28, 131–152 .